Circle Square Rectangle Class Python Drawing a Circle

Python

Object Oriented Programming (OOP)

I assume that y'all are familiar with the OOP concepts (such as form and example, limerick, inheritance and polymorphism), and yous know some OO languages such as Java/C++/C#. This commodity is not an introduction to OOP.

Python OOP Nuts

OOP Nuts

A class is a blueprint or template of entities (things) of the same kind. An instance is a particular realization of a grade.

Different C++/Java, Python supports both grade objects and instance objects. In fact, everything in Python is object, including class object.

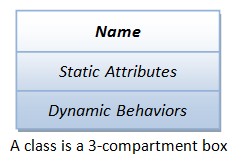

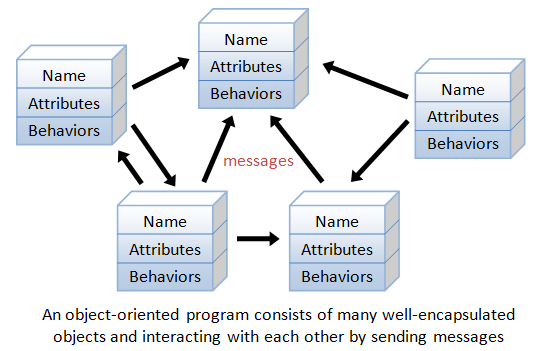

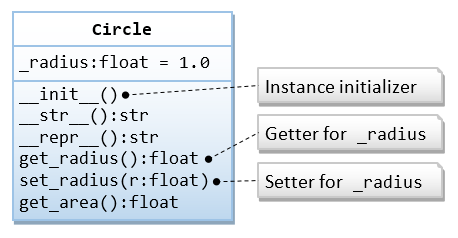

An object contains attributes: data attributes (or static attribute or variables) and dynamic behaviors chosen methods. In UML diagram, objects are represented by 3-compartment boxes: name, information attributes and methods, as shown below:

To access an attribute, use "dot" operator in the form of class_name.attr_name or instance_name.attr_name .

To construct an instance of a grade, invoke the constructor in the form of instance_name = class_name(args).

Case 1: Getting Started with a Circumvolve class

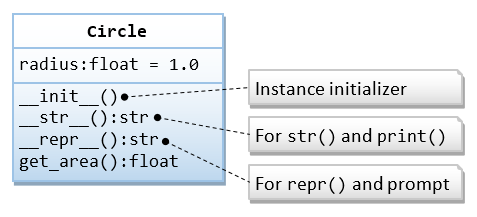

Let'southward write a module called circumvolve (to be saved equally circle.py), which contains a Circle class. The Circumvolve grade shall incorporate a data attribute radius and a method get_area(), as shown in the post-obit form diagram.

ane ii 3 four 5 half-dozen 7 viii 9 10 11 12 thirteen 14 fifteen 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 xxx 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 | from math import pi class Circle: def __init__(self, radius=1.0): cocky.radius = radius def __str__(self): return 'This is a circumvolve with radius of {:.2f}'.format(self.radius) def __repr__(self): return 'Circle(radius={})'.format(self.radius) def get_area(self): render self.radius * cocky.radius * pi if __name__ == '__main__': c1 = Circle(2.1) print(c1) print(c1.get_area()) print(c1.radius) print(str(c1)) print(repr(c1)) c2 = Circle() impress(c2) print(c2.get_area()) c2.color = 'red' print(c2.color) #print(c1.colour) # Error - c1 has no attribute color print(__doc__) print(Circle.__doc__) print(Circle.get_area.__doc__) print(isinstance(c1, Circle)) print(isinstance(c2, Circle)) impress(isinstance(c1, str)) |

Run this script, and check the outputs:

This is a circle with radius of ii.10 xiii.854423602330987 2.1 This is a circle with radius of ii.10 Circle(radius=2.one) This is a circle with radius of 1.00 three.141592653589793 crimson circle.py: The circle module, which defines a Circle grade. A Circle example models a circumvolve with a radius Return the expanse of this Circumvolve example True True Faux

How it Works

- Past convention, module names (and package names) are in lowercase (optionally joined with underscore if information technology improves readability). Form names are initial-capitalized (i.e., CamelCase). Variable and method names are also in lowercase.

Following the convention, this module is calledcircle(in lowercase) and is to exist saved as "circle.py" (the module name is the filename - in that location is no explicit fashion to proper noun a module). The course is calledCircle(in CamelCase). It contains a information attribute (instance variable)radiusand a methodget_area(). -

grade Circle:(Line 8): ascertain theCirclecourse.

NOTES: In Python ii, yous demand to write "class Circle(object):" to create a so-called new-manner course by inheriting from the default superclassobject. Otherwise, it will create a erstwhile-style class. The sometime-style classes should no longer exist used. In Python iii, "class Circle:" inherits fromobjectpast default. -

self(Line 11, 15, xix, 23): The first parameter of all the member methods shall be an object chosenself(eastward.g.,get_area(self),__init__(self, ...)), which binds to this instance (i.e., itself) during invocation. - You lot can invoke a method via the dot operator, in the form of

obj_name.method_name(). Still, Python differentiates between instance objects and class objects:- For class objects: Y'all can invoke a method via:

class_name .method_name(instance_name, ...)

where aninstance_nameis passed into the method every bit the argument'self'. - For instance objects: Python converts an instance method call from:

instance_name .method_name(...)

toclass_name .method_name( instance_name , ...)

where theinstance_nameis passed into the method as the argument'self'.

- For class objects: Y'all can invoke a method via:

- Constructor and

__init__()(Line 11): You can construct an instance of a course by invoking its constructor, in the grade ofclass_name(...), eastward.g.,c1 = Circumvolve(1.2) c2 = Circle()

Python commencement creates a plainCircumvolveobject. It and then invokes theCircle's__init__(self, radius)withselfbound to the newly created instance, equally follows:Circle.__init__(c1, 1.ii) Circle.__init__(c2)

Inside the__init__()method, theself.radius = radiuscreates and attaches an instance variableradiusunder the instancesc1andc2.

Take note that:-

__init__()is not really the constructor, only an initializer to create the example variables. -

__init__()shall never render a value. -

__init__()is optional and can be omitted if in that location is no instance variables.

-

- There is no need to declare example variables. The variable assignment statements in

__init__()create the instance variables. - Once example

c1was created, invocation of instance methodc1.get_area()(Line 33) is translated toCircle.getArea(c1)wherecockyis bound toc1. Within the method,self.radiusis bound toc1.radius, which was created during the initialization. - You tin can dynamically add together an attribute afterwards an object is constructed via assignment, as in

c2.colour='red'(Line 39). This is unlike other OOP languages like C++/Java. - You lot can identify dr.-string for module, class, and method immediately afterward their announcement. The doc-cord can exist retrieved via attribute

__doc__. Doc-strings are strongly recommended for proper documentation. - There is no "private" access control. All attributes are "public" and visible to all.

- [TODO] unit-test and doc-test

- [TODO] more

Inspecting the Example and Class Objects

Run the circumvolve.py script under the Python Interactive Beat out. The script creates ane class object Circumvolve and 2 instance objects c1 and c2.

$ cd /path/to/module_directory $ python3 >>> exec(open up('circumvolve.py').read()) ...... >>> dir() ['Circle', '__built-ins__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'c1', 'c2', 'pi'] >>> __name__ '__main__' >>> dir(c1) ['__class__', '__dict__', '__doc__', '__init__', '__str__', 'get_area', 'radius', ...] >>> vars(c1) {'radius': 2.one} >>> c1.__dict__ {'radius': 2.ane} >>> c1.__class__ <form '__main__.Circle'> >>> type(c1) <class '__main__.Circle'> >>> c1.__doc__ 'A Circle instance models a circle with a radius' >>> c1.__module__ '__main__' >>> c1.__init__ <jump method Circle.__init__ of Circle(radius=2.100000)> >>> c1.__str__ <jump method Circumvolve.__str__ of Circumvolve(radius=2.100000)> >>> c1.__str__() 'This is a circle with radius of 2.x' >>> c1.__repr__() 'Circle(radius=2.100000)' >>> c1 Circumvolve(radius=ii.100000) >>> c1.radius ii.ane >>> c1.get_area <bound method Circle.get_area of Circle(radius=2.100000)> >>> c1.get_area() 13.854423602330987 >>> dir(c2) ['color', 'get_area', 'radius', ...] >>> type(c2) <course '__main__.Circumvolve'> >>> vars(c2) {'radius': 1.0, 'color': 'red'} >>> c2.radius one.0 >>> c2.color 'red' >>> c2.__init__ <leap method Circle.__init__ of Circle(radius=one.000000)> >>> dir(Circle) ['__class__', '__dict__', '__doc__', '__init__', '__str__', 'get_area', ...] >>> help(Circle) ...... >>> Circle.__class__ <grade 'type'> >>> Circumvolve.__dict__ mappingproxy({'__init__': ..., 'get_area': ..., '__str__': ..., '__dict__': ..., '__doc__': 'A Circle example models a circle with a radius', '__module__': '__main__'}) >>> Circle.__doc__ 'A Circumvolve instance models a circle with a radius' >>> Circle.__init__ <function Circumvolve.__init__ at 0x7fb325e0cbf8> >>> Circle.__str__ <office Circle.__str__ at 0x7fb31f3ee268> >>> Circle.__str__(c1) 'This is a circle with radius of 2.x' >>> Circle.get_area <part Circle.get_area at 0x7fb31f3ee2f0> >>> Circle.get_area(c1) 13.854423602330987 Form Objects vs Instance Objects

As illustrated in the above example, there are 2 kinds of objects in Python's OOP model: grade objects and instance objects, which is quite different from other OOP languages.

Class objects provide default behavior and serve every bit factories for generating instance objects. Instance objects are the real objects created by your application. An instance object has its own namespace. It copies all the names from the class object from which it was created.

The class statement creates a course object of the given course name. Within the form definition, you can create class variables via assignment statements, which are shared by all the instances. You lot tin can likewise define methods, via the defs, to exist shared by all the instances.

When an instance is created, a new namespace is created, which is initially empty. It clones the class object and attaches all the class attributes. The __init__() is so invoked to create (initialize) instance variables, which are only available to this particular instance.

[TODO] more than

__str__() vs. __repr__()

The built-in functions print(obj) and str(obj) invoke obj.__str__() implicitly. If __str__() is not defined, they invoke obj.__repr__().

The born role repr(obj) invokes obj.__repr__() if divers; otherwise obj.__str__().

When you audit an object (east.g., c1) nether the interactive prompt, Python invokes obj.__repr__(). The default (inherited) __repr__() returns the obj 's address.

The __str__() is used for press an "informal" descriptive string of this object. The __repr__() is used to present an "official" (or canonical) cord representation of this object, which should look like a valid Python expression that could be used to re-create the object (i.e., eval(repr(obj)) == obj ). In our Circle class, repr(c1) returns 'Circle(radius=2.100000)'. You can employ "c1 = Circle(radius=ii.100000)" to re-create instance c1.

__str__() is meant for the users; while __repr__() is meant for the developers for debugging the programme. All classes should have both the __str__() and __repr__().

Yous could re-direct __repr__() to __str__() (but not recommended) as follows:

def __repr__(self): return cocky.__str__()

Import

Importing the circle module

When yous use "import circle", a namespace for circle is created under the current scope. You demand to reference the Circle class equally circle.Circle.

$ cd /path/to/module_directory $ python3 >>> import circumvolve >>> dir() ['__built-ins__', '__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'circle'] >>> dir(circle) ['Circle', '__built-ins__', '__doc__', '__name__', 'pi', ...] >>> dir(circle.Circle) ['__class__', '__doc__', '__init__', '__str__', 'get_area', ...] >>> __name__ '__main__' >>> circle.__name__ 'circle' >>> c1 = circle.Circumvolve(1.ii) >>> dir(c1) ['__class__', '__doc__', '__str__', 'get_area', 'radius', ...] >>> vars(c1) {'radius': one.2}

Importing the Circle class of the circumvolve module

When yous import the Circle course via "from circle import Circle", the Circle grade is added to the current telescopic, and you can reference the Circle course direct.

>>> from circumvolve import Circle >>> dir() ['Circle', '__built-ins__', '__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__'] >>> c1 = Circle(three.4) >>> vars(c1) {'radius': three.4} Class Definition Syntax

The syntax is:

class class_name ( superclass_1, ...): class_var_1 = value_1 ...... def __init__(cocky, arg_1, ...): self. instance_var_1 = arg_1 ...... def __str__(self): ...... def __repr__(self): ...... def method_name (self, *args, **kwargs ): ......

Case ii: The Betoken class and Operator Overloading

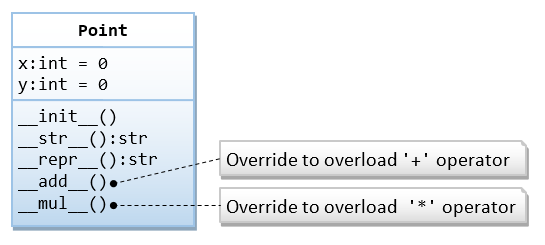

In this case, we shall define a Indicate class, which models a 2nd point with x and y coordinates. We shall likewise overload the operators '+' and '*' past overriding the so-called magic methods __add__() and __mul__().

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 xi 12 13 fourteen 15 16 17 18 xix 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 thirty 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 forty 41 42 43 44 45 46 | course Betoken: def __init__(self, 10 = 0, y = 0): cocky.x = x self.y = y def __str__(self): return '({}, {})'.format(cocky.x, cocky.y) def __repr__(self): """Return a control string to copy this instance""" render 'Betoken(ten={}, y={})'.format(self.ten, self.y) def __add__(self, right): p = Point(self.x + right.x, self.y + correct.y) return p def __mul__(self, factor): self.x *= factor cocky.y *= cistron return self if __name__ == '__main__': p1 = Bespeak() impress(p1) p1.x = 5 p1.y = 6 print(p1) p2 = Indicate(3, iv) print(p2) impress(p1 + p2) impress(p1) print(p2 * 3) print(p2) |

How it Works

- Python supports operator overloading (similar C++ but dissimilar Coffee). Yous can overload

'+','-','*','/','//'and'%'by overriding fellow member methods__add__(),__sub__(),__mul__(),__truediv__(),__floordiv__()and__mod__(), respectively. You tin overload other operators likewise (to be discussed later on). - In this example, the

__add__()returns a new instance; whereas the__mul__()multiplies into this instance and returns this instance, for bookish purpose.

The getattr(), setattr(), hasattr() and delattr() Congenital-in Functions

Y'all can admission an object'due south attribute via the dot operator by difficult-coding the attribute name, provided you lot know the attribute proper noun in compile time.

For example, yous can use:

-

obj_name.attr_name: to read an attribute -

obj_name.attr_name = value: to write value to an aspect -

del obj_name.attr_name: to delete an attribute

Alternatively, you tin can utilise built-in functions like getattr(), setattr(), delattr(), hasattr(), by using a variable to hold an attribute proper noun, which will exist leap during runtime.

-

hasattr(obj_name, attr_name) -> bool: returnsTrueif theobj_namecontains theatr_name. -

getattr(obj_name, attr_name[, default]) -> value: returns the value of theattr_nameof theobj_name, equivalent toobj_name.attr_name. If theattr_namedoes non exist, it returns thedefaultif present; otherwise, it raisesAttributeError. -

setattr(obj_name, attr_name, attr_value): sets a value to the attribute, equivalent toobj_name.attr_name = value. -

delattr(obj_name, attr_name): deletes the named attribute, equivalent todel obj_name.attr_name.

For example:

class MyClass: def __init__(self, myvar): self.myvar = myvar myinstance = MyClass(8) impress(myinstance.myvar) print(getattr(myinstance, 'myvar')) impress(getattr(myinstance, 'no_var', 'default')) attr_name = 'myvar' impress(getattr(myinstance, attr_name)) setattr(myinstance, 'myvar', ix) impress(getattr(myinstance, 'myvar')) print(hasattr(myinstance, 'myvar')) delattr(myinstance, 'myvar') print(hasattr(myinstance, 'myvar'))

Course Variable vs. Example Variables

Grade variables are shared by all the instances, whereas instance variables are specific to that item instance.

class MyClass: count = 0 def __init__(self): self.__class__.count += 1 self.id = cocky.__class__.count def get_id(self): return self.id def get_count(self): return self.__class__.count if __name__ == '__main__': print(MyClass.count) myinstance1 = MyClass() print(MyClass.count) print(myinstance1.get_id()) print(myinstance1.get_count()) print(myinstance1.__class__.count) myinstance2 = MyClass() print(MyClass.count) print(myinstance1.get_id()) print(myinstance1.get_count()) print(myinstance1.__class__.count) print(myinstance2.get_id()) impress(myinstance2.get_count()) print(myinstance2.__class__.count)

Individual Variables?

Python does not back up admission control. In other words, all attributes are "public" and are attainable past ALL. There is no "private" attributes like C++/Java.

However, by convention:

- Names begin with an underscore (

_) are meant for internal use, and are non recommended to exist accessed outside the form definition. - Names begin with double underscores (

__) and not end with double underscores are further hidden from direct access through proper name mangling (or rename). - Names begin and end with double underscores (such as

__init__,__str__,__add__) are special magic methods (to exist discussed after).

For case,

class MyClass: def __init__(self): cocky.myvar = ane self._myvar = 2 self.__myvar = three self.__myvar_ = 4 self.__myvar__ = 5 def print(self): print(cocky.myvar) print(cocky._myvar) print(self.__myvar) print(self.__myvar_) print(cocky.__myvar__) if __name__ == '__main__': myinstance1 = MyClass() print(myinstance1.myvar) impress(myinstance1._myvar) #impress(myinstance1.__myvar) # AttributeError #print(myinstance1.__myvar_) # AttributeError print(myinstance1.__myvar__) myinstance1.print() print(dir(myinstance1))

Class Method, Case Method and Static Method

Class Method (Decorator @classmethod)

A grade method belongs to the grade and is a function of the grade. It is declared with the @classmethod decorator. Information technology accepts the class every bit its first statement. For example,

>>> class MyClass: @classmethod def hello(cls): print('Hello from', cls.__name__) >>> MyClass.hello() Hello from MyClass >>> myinstance1 = MyClass() >>> myinstance1.how-do-you-do() Instance Method

Case methods are the most common blazon of method. An instance method is invoked by an example object (and non a course object). It takes the example (self) as its first argument. For instance,

>>> class MyClass: def hello(self): impress('Hello from', cocky.__class__.__name__) >>> myinstance1 = MyClass() >>> myinstance1.hello() Hello from MyClass >>> MyClass.hi() TypeError: how-do-you-do() missing one required positional argument: 'self' >>> MyClass.hello(myinstance1) Hello from MyClass Static Method (Decorator @staticmethod)

A static method is declared with a @staticmethod decorator. It "doesn't know its class" and is attached to the class for convenience. Information technology does not depends on the land of the object and could exist a separate function of a module. A static method can exist invoked via a grade object or instance object. For example,

>>> class MyClass: @staticmethod def hi(): print('Hello, world') >>> myinstance1 = MyClass() >>> myinstance1.hello() Hi, globe >>> MyClass.hello() Hello, world Example 3: Getter and Setter

In this example, we shall rewrite the Circle form to access the instance variable via the getter and setter. We shall rename the instance variable to _radius (meant for internal use only or private), with "public" getter get_radius() and setter set_radius(), as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 vii viii 9 ten 11 12 13 14 15 xvi 17 eighteen 19 twenty 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 xxx 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 | from math import pi form Circle: def __init__(cocky, _radius = ane.0): self.set_radius(_radius) def set_radius(self, _radius): if _radius < 0: raise ValueError('Radius shall exist non-negative') self._radius = _radius def get_radius(self): return self._radius def get_area(self): return self.get_radius() * self.get_radius() * pi def __repr__(cocky): return 'Circle(radius={})'.format(self.get_radius()) if __name__ == '__main__': c1 = Circle(i.2) impress(c1) impress(vars(c1)) impress(c1.get_area()) print(c1.get_radius()) c1.set_radius(3.4) print(c1) c1._radius = 5.6 print(c1) c2 = Circle() print(c2) c3 = Circle(-5.6) |

How information technology Works

- While there is no concept of "private" attributes in Python, we could yet rewrite our

Circleclass with "public" getter/setter, equally in the above instance. This is ofttimes done because the getter and setter need to deport out certain processing, such as information conversion in getter, or input validation in setter. - Nosotros renamed the instance variable

_radius(Line nine), with a leading underscore to announce it "individual" (but information technology is still attainable to all). According to Python naming convention, names start with a underscore are to exist treated as "private", i.e., it shall not exist used outside the class. We named our "public" getter and setterget_radius()andset_radius(), respectively. - In the constructor, we invoke the setter to set up the instance variable (Line thirteen), instead of assign directly, as the setter may perform tasks like input validation. Similarly, nosotros use the getter in

get_area()(Line 27) and__repr__()(Line 32).

Case iv: Creating a belongings object via the belongings() Built-in Function

Add the following into the Circle class in the previous case:

class Circle: ...... radius = property(get_radius, set_radius)

This creates a new belongings object (instance variable) called radius, with the given getter/setter (which operates on the existing case variable _radius). Recall that we have renamed our instance variable to _radius, then they do not crash.

You tin can now use this new property radius, just like an ordinary instance variable, e.g.,

c1 = Circle(1.ii) print(c1.radius) c1.radius = 3.4 impress(c1.radius) print(vars(c1)) print(dir(c1)) c1._radius = five.half-dozen print(c1._radius) c1.set_radius(7.8) print(c1.get_radius()) impress(type(c1.radius)) print(type(c1._radius)) print(type(Circle.radius)) print(type(Circle._radius))

The born function property() has the post-obit signature:

property(fn_get=None, fn_set=None, fn_del=None, dr.=None)

You can specify a delete role, as well as a dr.-cord. For example,

class Circle: ...... def del_radius(cocky): del self._radius radius = property(get_radius, set_radius, del_radius, "Radius of this circle")

More on property object

[TODO]

Case v: Creating a property via the @property Decorator

In the above case, the argument:

radius = property(get_radius, set_radius, del_radius)

is equivalent to:

radius = property() radius.getter(cocky.get_radius) radius.setter(cocky.set_radius) radius.deleter(self.del_radius)

These can be implemented via decorators @property, @varname.setter and @varname.deleter, respectively. For example,

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 sixteen 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 | from math import pi form Circle: def __init__(self, radius = 1.0): self.radius = radius @property def radius(self): return self._radius @radius.setter def radius(self, radius): if radius < 0: raise ValueError('Radius shall be not-negative') self._radius = radius @radius.deleter def radius(cocky): del self._radius def get_area(cocky): return self.radius * self.radius * pi def __repr__(self): render 'Circumvolve(radius={})'.format(self.radius) if __name__ == '__main__': c1 = Circle(1.2) print(c1) print(vars(c1)) print(dir(c1)) c1.radius = 3.four impress(c1.radius) print(c1._radius) #print(c1.get_radius()) # AttributeError: 'Circle' object has no attribute 'get_radius' c2 = Circle() impress(c2) c3 = Circle(-5.half dozen) |

How it Works

- We use a hidden example variable called

_radiusto store the radius, which is set in the setter, subsequently input validation. - We renamed the getter from

get_radius()toradius, and used the decorator@holdingto decorate the getter. - We as well renamed the setter from

set_radius()toradius, and utilise the decorator@radius.setterto decorate the setter. - [TODO] more

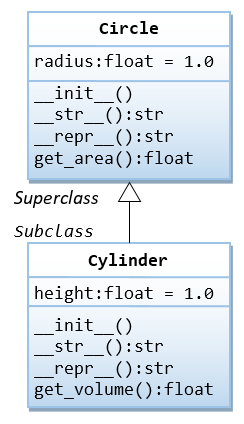

Inheritance and Polymorphism

Example six: The Cylinder grade every bit a subclass of Circle course

In this case, we shall define a Cylinder class, as a bracket of Circle. The Cylinder course shall inherit attributes radius and get_area() from the superclass Circumvolve, and add together its own attributes height and get_volume().

1 two 3 4 five 6 seven 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 xv 16 17 18 nineteen 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 thirty 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 forty 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 sixty 61 62 63 64 65 | from circumvolve import Circumvolve form Cylinder(Circle): def __init__(self, radius = 1.0, height = i.0): super().__init__(radius) self.height = acme def __str__(self): return 'Cylinder(radius={},height={})'.format(cocky.radius, cocky.height) def __repr__(cocky): return self.__str__() def get_volume(self): return self.get_area() * cocky.acme if __name__ == '__main__': cy1 = Cylinder(i.1, 2.ii) print(cy1) print(cy1.get_area()) print(cy1.get_volume()) impress(cy1.radius) impress(cy1.height) print(str(cy1)) print(repr(cy1)) cy2 = Cylinder() print(cy2) print(cy2.get_area()) print(cy2.get_volume()) print(dir(cy1)) print(Cylinder.get_area) print(Circumvolve.get_area) print(issubclass(Cylinder, Circle)) print(issubclass(Circle, Cylinder)) print(isinstance(cy1, Cylinder)) impress(isinstance(cy1, Circle)) impress(Cylinder.__base__) print(Circle.__subclasses__()) c1 = Circle(3.three) impress(c1) print(isinstance(c1, Circle)) print(isinstance(c1, Cylinder)) |

How information technology works?

- When you construct a new example of

Cylindervia:cy1 = Cylinder(one.1, 2.2)

Python showtime creates a plainlyCylinderobject and invokes theCylinder'south__init__()withcockybinds to the newly createdcy1, as follows:Cylinder.__init__(cy1, ane.1, two.2)

Within the__init__(), thesuper().__init__(radius)invokes the superclass'__init__(). (You tin also explicitly phone callCircumvolve.__init__(self, radius)just you demand to hardcode the superclass' name.) This creates a superclass instance withradius. The next argumentself.pinnacle = pinnaclecreates the example variableheightforcy1.

Take note that Python does not call the superclass' constructor automatically (unlike Java/C++). - If

__str__()or__repr__()is missing in the bracket,str()andrepr()will invoke the superclass version. Endeavor commenting out__str__()and__repr__()and check the results.

super()

In that location are ii ways to invoke a superclass method:

- via explicit classname: e.k.,

Circumvolve.__init__(self) Circle.get_area(self)

- via

super(): eastward.yard.,super().__init__(radius) super(Cylinder, self).__init__(radius) super().get_area() super(Cylinder, self).get_area()

Y'all tin can avoid hard-coding the superclass' proper name with super(). This is recommended, especially in multiple inheritance as it can resolve some conflicts (to exist discussed later).

The super() method returns a proxy object that delegates method calls to a parent or sibling course. This is useful for accessing inherited methods that have been overridden in a class.

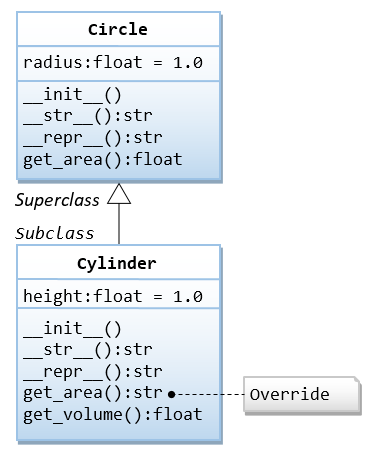

Example 7: Method Overriding

In this case, we shall override the get_area() method to render the surface area of the cylinder. Nosotros also rewrite the __str__() method, which also overrides the inherited method. We demand to rewrite the get_volume() to utilize the superclass' get_area(), instead of this class.

1 2 3 4 v 6 7 eight 9 x eleven 12 13 14 fifteen 16 17 18 nineteen xx 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 xl 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 | from math import pi from circle import Circle # Using the Circumvolve course in the circle module course Cylinder(Circle): def __init__(cocky, radius = 1.0, height = ane.0): super().__init__(radius) self.tiptop = peak def __str__(self): return 'Cylinder({}, height={})'.format(super().__repr__(), cocky.height) def __repr__(self): return self.__str__() def get_area(self): return 2.0 * pi * cocky.radius * cocky.summit def get_volume(self): return super().get_area() * self.tiptop if __name__ == '__main__': cy1 = Cylinder(one.one, 2.2) print(cy1) print(cy1.get_area()) print(cy1.get_volume()) impress(cy1.radius) print(cy1.height) print(str(cy1)) print(repr(cy1)) cy2 = Cylinder() print(cy2) print(cy2.get_area()) print(cy2.get_volume()) print(dir(cy1)) print(Cylinder.get_area) impress(Circle.get_area) |

- In Python, the overridden version replaces the inherited version, every bit shown in the in a higher place role references.

- To access superclass' version of a method, use:

- For Python 3:

super().method_name(*args), e.thousand.,super().get_area() - For Python 2:

super(this_class, self).method_name(*args), e.k.,super(Cylinder, self).get_area() - Explicitly via the course name:

superclass.method-name(self, *args), e.g.,Circle.get_area(self)

- For Python 3:

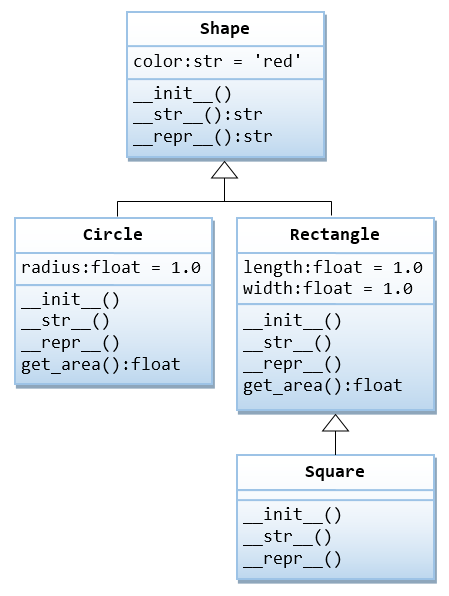

Example 8: Shape and its subclasses

1 2 three 4 5 6 vii eight 9 x eleven 12 13 fourteen 15 16 17 18 xix 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 fifty 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 sixty 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 lxx 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 fourscore 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 | course Shape: def __init__(self, colour = 'blood-red'): cocky.color = color def __str__(self): render 'Shape(color={})'.format(self.colour) def __repr__(cocky): render self.__str__() form Circle(Shape): def __init__(self, radius = 1.0, colour = 'red'): super().__init__(color) self.radius = radius def __str__(self): return 'Circumvolve({}, radius={})'.format(super().__str__(), cocky.radius) def __repr__(self): return cocky.__str__() def get_area(cocky): return self.radius * self.radius * pi class Rectangle(Shape): def __init__(self, length = i.0, width = 1.0, colour = 'red'): super().__init__(color) self.length = length self.width = width def __str__(self): return 'Rectangle({}, length={}, width={})'.format(super().__str__(), self.length, self.width) def __repr__(cocky): return self.__str__() def get_area(self): return cocky.length * self.width class Square(Rectangle): def __init__(self, side = one.0, color = 'red'): super().__init__(side, side, color) def __str__(self): return 'Square({})'.format(super().__str__()) if __name__ == '__main__': s1 = Shape('orange') print(s1) impress(s1.color) print(str(s1)) print(repr(s1)) c1 = Circle(i.two, 'orange') print(c1) impress(c1.get_area()) print(c1.color) print(c1.radius) impress(str(c1)) print(repr(c1)) r1 = Rectangle(1.2, 3.4, 'orange') print(r1) print(r1.get_area()) print(r1.colour) impress(r1.length) print(r1.width) print(str(r1)) print(repr(r1)) sq1 = Square(5.half dozen, 'orange') print(sq1) print(sq1.get_area()) impress(sq1.color) print(sq1.length) print(sq1.width) impress(str(sq1)) print(repr(sq1)) |

Multiple Inheritance

Python supports multiple inheritance, which is defined in the grade of "class class_name(base_class_1, base_class_2,...):".

Mixin Blueprint

The simplest and nearly useful blueprint of multiple inheritance is called mixin. A mixin is a superclass that is not meant to exist on its ain, only meant to be inherited by some sub-classes to provide actress functionality.

[TODO]

Diamond Problem

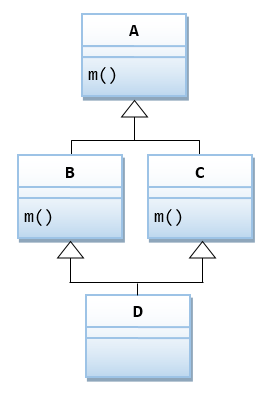

Suppose that two classes B and C inherit from a superclass A, and D inherits from both B and C. If A has a method called m(), and m() is overridden by B and/or C, and then which version of chiliad() is inherited by D?

Let's wait at Python'south implementation.

Example 1

class A: def k(cocky): print('in Class A') class B(A): def m(self): print('in Class B') class C(A): def m(self): impress('in Form C') class D1(B, C): pass form D2(C, B): pass grade D3(B, C): def m(self): print('in Class D3') if __name__ == '__main__': 10 = D1() x.m() ten = D2() x.thou() 10 = D3() ten.m() Case two

Suppose the overridden m() in B and C invoke A's grand() explicitly.

class A: def m(self): print('in Course A') course B(A): def m(self): A.k(self) print('in Course B') class C(A): def 1000(self): A.m(cocky) print('in Grade C') class D(B, C): def m(self): B.thou(self) C.m(self) impress('in Class D') if __name__ == '__main__': x = D() x.m() The output is:

in Class A in Class B in Grade A in Class C in Class D

Take note that A'south m() is run twice, which is typically not desired. For example, suppose that one thousand() is the __init__(), then A volition be initialized twice.

Example 3: Using super()

form A: def one thousand(cocky): impress('in Class A') class B(A): def m(self): super().k() impress('in Class B') grade C(A): def m(self): super().m() print('in Class C') class D(B, C): def 1000(self): super().m() impress('in Class D') if __name__ == '__main__': 10 = D() x.m() in Class A in Form C in Grade B in Class D

With super(), A's m() is simply run once. This is because super() uses the so-called Method Resolution Order (MRO) to linearize the superclass. Hence, super() is strongly recommended for multiple inheritance, instead of explicit class telephone call.

Example 4: Permit'south look at __init__()

class A: def __init__(self): print('init A') class B(A): def __init__(self): super().__init__() impress('init B') class C(A): def __init__(self): super().__init__() print('init C') class D(B, C): def __init__(self): super().__init__() impress('init D') if __name__ == '__main__': d = D() c = C() b = B() Each superclass is initialized exactly once, as desired.

Yous tin check the MRO via the mro() member method:

>>> D.mro() [<class '__main__.D'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <course '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class 'object'>] >>> C.mro() [<form '__main__.C'>, <form '__main__.A'>, <form 'object'>] >>> B.mro() [<course '__main__.B'>, <grade '__main__.A'>, <class 'object'>]

Abstruse Methods

An abstract method has no implementation, and therefore cannot exist called. The subclasses shall overrides the abstract methods inherited and provides their own implementations.

In Python 3, you can use decorator @abstractmethod to marker an abstruse method. For example,

@abstractmethod def method_name(self, ...): pass [TODO] more

Polymorphism

Polymorphism in OOP is the power to nowadays the same interface for differing underlying implementations. For instance, a polymorphic role tin can be applied to arguments of different types, and it behaves differently depending on the blazon of the arguments to which they are applied.

Python is implicitly polymorphic, as type are associated with objects instead of variable references.

[TODO] more

Avant-garde OOP in Python

Magic Methods

A magic method is an object'south fellow member methods that begins and ends with double underscore, e.g., __init__(), __str__(), __repr__(), __add__(), __len__().

Equally an example, we listing the magic methods in the int class:

>>> dir(int) ['__abs__', '__add__', '__and__', '__bool__', '__ceil__', ...]

In Python, born operators and functions invoke the corresponding magic methods. For example, operator '+' invokes __add__(), born office len() invokes __len__(). Fifty-fifty though the magic methods are invoked implicitly via born operators and functions, you can also call them explicitly, e.g., 'abc'.__len__() is the same as len('abc').

The post-obit table summarizes the unremarkably-used magic methods and their invocation.

| Magic Method | Invoked Via | Invocation Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| __lt__(self, correct) __gt__(cocky, right) __le__(self, correct) __ge__(cocky, right) __eq__(self, right) __ne__(self, right) | Comparison Operators | self < right self > right self <= right cocky >= right self == correct self != right |

| __add__(cocky, right) __sub__(cocky, right) __mul__(self, correct) __truediv__(self, correct) __floordiv__(self, right) __mod__(cocky, correct) __pow__(self, right) | Arithmetic Operators | self + right self - right cocky * correct self / right cocky // right self % right self ** right |

| __and__(cocky, correct) __or__(self, right) __xor__(self, right) __invert__(self) __lshift__(cocky, north) __rshift__(self, north) | Bitwise Operators | self & right self | correct self ^ right ~self self << north self >> n |

| __str__(self) __repr__(self) __sizeof__(self) | Built-in Office Call | str(self), print(self) repr(self) sizeof(self) |

| __len__(self) __contains__(cocky, particular) __iter__(cocky) __next__(self) __getitem__(self, key) __setitem__(self, cardinal, value) __delitem__(self, key) | Sequence Operators & Born Functions | len(cocky) item in self iter(self) side by side(self) self[cardinal] self[central] = value del self[key] |

| __int__(self) __float__(self) __bool__(self) __oct__(self) __hex__(self) | Type Conversion Built-in Function Call | int(self) float(self) bool(self) oct(self) hex(self) |

| __init__(self, *args) __new__(cls, *args) | Constructor / Initializer | x = ClassName(*args) |

| __del__(self) | Operator del | del x |

| __index__(cocky) | Catechumen this object to an index | x[cocky] |

| __radd__(self, left) __rsub__(self, left) ... | RHS (Reflected) addition, subtraction, etc. | left + cocky left - self ... |

| __iadd__(cocky, correct) __isub__(self, right) ... | In-identify add-on, subtraction, etc | self += right self -= correct ... |

| __pos__(self) __neg__(self) | Unary Positive and Negate operators | +self -cocky |

| __round__(self) __floor__(cocky) __ceil__(self) __trunc__(self) | Office Call | round(self) floor(self) ceil(self) trunc(self) |

| __getattr__(self, proper name) __setattr__(self, proper noun, value) __delattr__(self, proper noun) | Object'due south attributes | cocky.name cocky.name = value del self.proper noun |

| __call__(self, *args, **kwargs) | Callable Object | obj(*args, **kwargs); |

| __enter__(self), __exit__(self) | Context Managing director with-argument |

Construction and Initialization

When yous use x = ClassName(*args) to construct an instance of 10, Python beginning calls __new__(cls, *args) to create an instance, it then invokes __init__(self, *args) (the initializer) to initialize the instance.

Operator Overloading

Python supports operators overloading (like C++) via overriding the respective magic functions.

Example

To Override the '==' operator for the Circle class:

grade Circle: def __init__(self, radius): self.radius = radius def __eq__(self, right): if self.__class__.__name__ == right.__class__.__name__: render self.radius == right.radius heighten TypeError("not a 'Circle' object") if __name__ == '__main__': print(Circumvolve(8) == Circumvolve(viii)) impress(Circumvolve(8) == Circle(88)) print(Circle(8) == 'abc') [TODO] more than examples

Iterable and Iterator: iter() and next()

Python iterators are supported by two magic member methods: __iter__(self) and __next__(self).

- The Iterable object (such as list) shall implement the

__iter__(self)member method to return an iterator object. This method tin can be invoked explicitly via "iterable.__iter__()", or implicitly via "iter(iterable)" or "for item in iterable" loop. - The returned iterator object shall implement the

__next__(self)method to return the next particular, or heightenStopIerationif there is no more detail. This method can exist invoked explicitly via "iterator.__next__()", or implicitly via "adjacent(iterator)" or within the "for detail in iterable" loop.

Example 1:

A list is an iterable that supports iterator.

>>> lst_itr = iter([xi, 22, 33]) >>> lst_itr <list_iterator object at 0x7f945e438550> >>> side by side(lst_itr) 11 >>> next(lst_itr) 22 >>> next(lst_itr) 33 >>> next(lst_itr) ...... StopIteration >>> lst_itr2 = [44, 55].__iter__() >>> lst_itr2 <list_iterator object at 0x7f945e4385f8> >>> lst_itr2.__next__() 44 >>> lst_itr2.__next__() 55 >>> lst_itr2.__next__() StopIteration >>> for item in [11, 22, 33]: print(item)

Example 2:

Let's implement our own iterator. The following RangeDown(min, max) is similar to range(min, max + i), but counting down. In this example, the iterable and iterator are in the aforementioned class.

class RangeDown: def __init__(self, min, max): self.electric current = max + 1 self.min = min def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): self.electric current -= ane if cocky.current < self.min: raise StopIteration else: return self.electric current if __name__ == '__main__': itr = iter(RangeDown(six, eight)) print(next(itr)) print(side by side(itr)) print(adjacent(itr)) #print(side by side(itr)) for i in RangeDown(6, viii): print(i, end=" ") impress() itr2 = RangeDown(9, 10).__iter__() print(itr2.__next__()) print(itr2.__next__()) print(itr2.__next__())

Example 3:

Let's separate the iterable and iterator in 2 classes.

class RangeDown: def __init__(cocky, min, max): self.min = min self.max = max def __iter__(self): return RangeDownIterator(self.min, self.max) form RangeDownIterator: def __init__(self, min, max): self.min = min self.current = max + one def __next__(self): self.current -= 1 if self.current < self.min: heighten StopIteration else: return cocky.current if __name__ == '__main__': itr = iter(RangeDown(6, eight)) impress(next(itr)) print(next(itr)) print(side by side(itr)) #print(next(itr))

Generator and yield

A generator role is a function that can produce a sequence of results instead of a single value. A generator function returns a generator iterator object, which is a special blazon of iterator where you can obtain the adjacent elements via side by side().

A generator function is like an ordinary office, but instead of using render to render a value and leave, information technology uses yield to produce a new outcome. A function which contains yield is automatically a generator function.

Generators are useful to create iterators.

Example one: A Simple Generator

>>> def my_simple_generator(): yield(11) yield(22) yield(33) >>> g1 = my_simple_generator() >>> g1 <generator object my_simple_generator at 0x7f945e441990> >>> next(g1) 11 >>> adjacent(g1) 22 >>> next(g1) 33 >>> adjacent(g1) ...... StopIteration >>> for item in my_simple_generator(): print(item, finish=' ') eleven 22 33

Instance 2

The following generator office range_down(min, max) implements the count-down version of range(min, max+1).

>>> def range_down(min, max): current = max while current >= min: yield current current -= 1 >>> range_down(5, 8) <generator object range_down at 0x7f5e34fafc18> >>> for i in range_down(5, 8): print(i, end=" ") >>> itr = range_down(2, 4) >>> itr <generator object range_down at 0x7f230d53a168> >>> next(itr) iv >>> side by side(itr) 3 >>> next(itr) ii >>> next(itr) StopIteration >>> itr2 = range_down(5, half-dozen).__iter__() >>> itr2 <generator object range_down at 0x7f230d53a120> >>> itr2.__next__() 6 >>> itr2.__next__() v >>> itr2.__next__() StopIteration

Each fourth dimension the yield statement is run, it produce a new value, and updates the land of the generator iterator object.

Case 3

We can have generators which produces space value.

from math import sqrt, ceil def gen_primes(number): while True: if is_prime(number): yield number number += 1 def is_prime(number:int) -> int: if number <= 1: return False cistron = 2 while (factor <= ceil(sqrt(number))): if number % factor == 0: return False cistron += 1 return Truthful if __name__ == '__main__': grand = gen_primes(8) for i in range(100): print(next(k))

Generator Expression

A generator expression has a similar syntax as a list/dictionary comprehension (for generating a list/dictionary), but surrounded by braces and produce a generator iterator object. (Note: braces are used past tuples, but they are immutable and thus cannot be comprehended.) For example,

>>> a = (x*x for x in range(i,5)) >>> a <generator object <genexpr> at 0x7f230d53a2d0> >>> for item in a: impress(item, terminate=' ') 1 4 ix xvi >>> sum(a) xxx >>> b = (x*x for x in range(1, 10) if x*10 % two == 0) >>> for item in b: print(item, cease=' ') 4 xvi 36 64 >>> lst = [x*10 for x in range(ane, x)] >>> lst [1, four, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81] >>> dct = {x:10*x for ten in range(1, 10)} >>> dct {1: ane, two: four, three: 9, four: xvi, five: 25, six: 36, vii: 49, 8: 64, 9: 81} Callable: __call__()

In Python, you can call an object to execute some codes, just like calling a role. This is done by providing a __call__() member method. For instance,

course MyCallable: def __init__(self, value): self.value = value def __call__(self): return 'The value is %s' % self.value if __name__ == '__main__': obj = MyCallable(88) print(obj())

Context Director: __enter__() and __exit__()

[TODO]

Unit Testing

Testing is CRTICALLY IMPORTANT in software development. Some people really advocate "Write Test Get-go (before writing the codes)" (in and then chosen Exam-Driven Development (TDD)). You should at least write your tests along side your development.

In python, you can carry out unit testing via built-in modules unittest and doctest.

unittest Module

The unittest module supports all features needed to run unit of measurement tests:

- Test Instance: contains a set of test methods, supported by

testunit.TestCaseclass. - Examination Suite: a collection of test cases, or test suites, or both; supported by

testunit.TestSuiteform. - Test Fixture: Items and preparations needed to run a test; supported via the

setup()andtearDown()methods inunittest.TestCasegrade. - Exam Runner: run the tests and report the results; supported via

unittest.TestRunner,unittest.TestResult, etc.

Example ane: Writing Examination Instance

import unittest def my_sum(a, b): return a + b class TestMySum(unittest.TestCase): def test_positive_inputs(self): result = my_sum(8, eighty) cocky.assertEqual(result, 88) def test_negative_inputs(self): consequence = my_sum(-ix, -90) cocky.assertEqual(result, -99) def test_mixed_inputs(self): result = my_sum(8, -9) self.assertEqual(result, -1) def test_zero_inputs(self): result = my_sum(0, 0) self.assertEqual(outcome, 0) if __name__ == '__main__': unittest.primary()

The expected outputs are:

.... ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran iv tests in 0.001s OK

How it Works

- Y'all tin create a test case by sub-classing

unittest.TestCase. - A test example contains test methods. The test method names shall begin with

test. - You tin can use the generic

assertstatement to compare the test outcome with the expected result:assert examination, [msg]

- You can likewise use the

assertXxx()methods provided byunittest.TestCaseform. These method takes an optional statementmsgthat holds a message to be display if exclamation fails. For examples,-

assertEqual(a, b, [msg]):a == b -

assertNotEqual(a, b, [msg]):a != b -

assertTrue(a, [msg]):bool(x)isTrue -

assertFalse(a, [msg]):bool(10)isFalse -

assertIsNone(expr, [msg]):10 is None -

assertIsNotNone(expr, [msg]):x is non None -

assertIn(a, b, [msg]):a in b -

assertNotIn(a, b, [msg]):a not in b -

assertIs(obj1, obj2, [msg]):obj1 is obj2 -

assertIsNot(obj1, obj2, [msg]):obj1 is not obj2 -

assertIsInstance(obj, cls, [msg]):isinstance(obj, cls) -

assertIsNotInstance(obj, cls, [msg]):non isinstance(obj, cls) -

assertGreater(a, b, [msg]):a > b -

assertLess(a, b, [msg]):a < b -

assertGreaterEqual(a, b, [msg]):a >= b -

assertLessEqual(a, b, [msg]):a <= b -

assertAlmostEqual(a, b, [msg]):circular(a-b, vii) == 0 -

assertNotAlmostEqual(a, b, [msg]):round(a-b, 7) != 0 -

assertRegex(text, regex, [msg]):regex.search(text) -

assertNotRegex(text, regex, [msg]):not regex.search(text) -

assertDictEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertListEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertTupleEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertSetEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertSequenceEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertItemsEqual(a, b, [msg]): -

assertDictContainsSubset(a, b, [msg]): -

assertRaises(except, func, *args, **kwargs):func(*args, **kwargs)raisesexcept - Many more, meet the

unittestAPI documentation.

-

- Exam cases and examination methods run in alphanumeric club.

Example 2: Setting upwardly Test Fixture

Yous can setup your examination fixtures, which are available to all the text methods, via setUp(), tearDown(), setUpClass() and tearDownClass() methods. The setUp() and tearDown() will be executed before and after EACH test method; while setUpClass() and tearDownClass() volition be executed before and afterward ALL examination methods in this test class.

For example,

import unittest class MyTestClass(unittest.TestCase): @classmethod def setUpClass(cls): print('run setUpClass()') @classmethod def tearDownClass(cls): print('run tearDownClass()') def setUp(self): print('run setUp()') def tearDown(self): impress('run tearDown()') def test_numbers_equal(self): print('run test_numbers_equal()') cocky.assertEqual(viii, 8) def test_numbers_not_equal(self): print('run test_numbers_not_equal()') self.assertNotEqual(eight, -8) if __name__ == '__main__': unittest.principal() The expected outputs are:

Finding files... done. Importing test modules ... done. run setUpClass() run setUp() run test_numbers_equal() run tearDown() run setUp() run test_numbers_not_equal() run tearDown() run tearDownClass() ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 2 tests in 0.001s OK

[TODO] An Example to setup text fixtures for each examination method.

Example 3: Using Test Suite

You tin can organize your exam cases into test suites. For example,

def my_suite1(): suite = unittest.TestSuite() suite.addTest(MyTestCase('test_method1')) suite.addTest(MyTestCase('test_method2')) return suite my_suite2 = unittest.TestLoader().loadTestsFromTestCase(MyTestCase) if __name__ == "__main__": runner = unittest.TextTestRunner() runner.run(my_suite1()) runner.run(my_suite2) Skipping Tests

Employ unittest.skip([msg]) decorator to skip ane exam, eastward.g.,

@unittest.skip('msg') def test_x(): ...... Invoke instance method skipTest([msg]) inside the test method to skip the test, east.thou.,

def test_x(): cocky.skipTest() ......

You can use decorator unittest.skipIf(status, [msg]), @unittest.skipUnless(condition, [msg]), for provisional skip.

Fail Examination

To fail a test, use instance method fail([msg]).

doctest Module

Embed the examination input/output pairs in the doc-string, and invoke doctest.testmod(). For example,

import doctest def my_sum(a, b): """ (number, number) -> number Return a + b For use by doctest: >>> my_sum(8, fourscore) 88 >>> my_sum(-9, -90) -99 >>> my_sum(8, -9) -1 >>> my_sum(0, 0) 0 """ return a + b if __name__ == '__main__': doctest.testmod(verbose=1)

Study the outputs:

Trying: my_sum(8, fourscore) Expecting: 88 ok Trying: my_sum(-nine, -90) Expecting: -99 ok Trying: my_sum(8, -9) Expecting: -ane ok Trying: my_sum(0, 0) Expecting: 0 ok 1 items had no tests: __main__ 1 items passed all tests: 4 tests in __main__.my_sum 4 tests in 2 items. 4 passed and 0 failed. Exam passed.

The "(number, number) -> number" is known as type contract, which spells out the expected types of the parameters and return value.

Functioning Measurement

You can use modules timeit, profile and pstats for profiling Python program and operation measurements.

[TODO] examples

Yous could measure code coverage via coverage module.

[TODO] examples

REFERENCES & Resource

- The Python's mother site @ www.python.org; "The Python Documentation" @ https://www.python.org/md/; "The Python Tutorial" @ https://docs.python.org/tutorial/; "The Python Linguistic communication Reference" @ https://docs.python.org/reference/.

Latest version tested: Python (Ubuntu, Windows, Cygwin) 3.7.1 and two.7.14

Terminal modified: Nov, 2018

Source: https://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/webprogramming/Python1a_OOP.html

Enregistrer un commentaire for "Circle Square Rectangle Class Python Drawing a Circle"